Interactive tool for asthma patients to help self-assessment

[et_pb_section fb_built="1" _builder_version="4.22.1" _module_preset="default" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="et_body_layout"][et_pb_row _builder_version="4.22.1" _module_preset="default" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="et_body_layout"][et_pb_column type="4_4" _builder_version="4.22.1" _module_preset="default" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="et_body_layout"][et_pb_text _builder_version="4.22.2" _module_preset="default" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="et_body_layout"]

Asthma is a complex disease with many different causes & triggers. Sometimes asthma symptoms gradually get worse despite all efforts to control them, and one way that happens is when someone becomes allergic to Aspergillus. Allergic BronchoPulmonary Aspergillosis (ABPA) and Severe asthma with fungal sensitisation (SAFS) are two possible outcomes. This progression usually happens slowly and gradually so it is difficult to tell when the allergy began. This tool can help you assess if you need more help from your doctors, and what help may be available.

Asthma + Lung UK has developed an interactive tool to enable people with poorly controlled asthma to self-assess their likelihood of having severe asthma and ask for the support they need. This can be a useful way to find out if you could benefit from biologics (or other therapy).

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

Do you need a Patient Information Leaflet for your medication?

[et_pb_section fb_built="1" _builder_version="4.22.1" _module_preset="default" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="et_body_layout"][et_pb_row _builder_version="4.22.1" _module_preset="default" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="et_body_layout"][et_pb_column type="4_4" _builder_version="4.22.1" _module_preset="default" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="et_body_layout"][et_pb_text _builder_version="4.22.2" _module_preset="default" theme_builder_area="et_body_layout" hover_enabled="0" sticky_enabled="0"]

Patient Information leaflets (PIL) are meant to be enclosed with every pack of medication, in fact, it is a legal requirement unless all the relevant information is on the packaging. The PIL must contain all the information needed for a patient to be able to take the medication safely and effectively, so the leaflet includes details of dose, how to take the medication, side effects, and much more. It is strongly suggested that the patient read through all the information before taking the medication, especially if it is the first time that the patient has taken the enclosed drug.

Despite the law, there may be reasons why you might not have received a PIL with your latest drug. Sometimes a pack has been split by the pharmacist between more than one patient for example. If you need a PIL and you didn't receive one you can return to your pharmacist who should be able to source one for you, and for those who have access to the internet, you can also find a PIL for all medications online.

Go to medicines.org.uk and search for your prescription drug. The documents on this website are fully verified by UK govenment authorities.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

Unvalidated Laboratory Testing

Commercial laboratories can sell their diagnostic tests directly to the public, or they can be ordered by non-NHS providers of healthcare. The reasons given can sound very persuasive about how useful those test results can be - for example, testing for organic acids in your urine to check your nutritional status or testing for mycotoxins in your urine to assess if you have been exposed to excessive airborne mould spores. Unfortunately, these results are often useless for the purpose intended.

It is important that testing is validated for clinical use for the purpose it is being used for, for example:

- An Organic acid profile in urine is validated and used by the NHS for testing patients for very rare genetic problems that lead to an accumulation of an organic acid and a deficiency in certain cellular products. These levels are likely to be high and the result is clear and consistent from test to test. These tests are likely to be carried in in very young children who have inherited an abnormal gene. https://www.southtees.nhs.uk/services/pathology/tests/organic-acids-urine/.

- An Organic acid profile in urine is NOT validated to run on adults who have a normal genetic profile and have no signs or symptoms of metabolic disease. The results are going to need highly specialised doctors to interpret the results. If used for the purpose of, for example, assessing the nutritional status of a patient there is no evidence that the result will tell you or your doctor anything useful. Consequently these are very unlikely to be worth the cost.

If you are tempted to purchase one of these tests it is well worth checking this website for advice https://labtestsonline.org.uk/tests/unvalidated-or-misleading-laboratory-tests

Osteoporosis (Thinning bones)

Many people with aspergillosis are vulnerable to osteoporosis, partly due to some of the medication they take, partly due to their genetics and partly age.

There is a complete guide for the treatment of osteoporosis by the NHS at the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) called Osteoporosis - prevention of fragility fractures and you can read it here.

However, you may prefer the easier-to-read guidelines offered by the Royal Osteoporosis Society which is comprehensive and excellent. There is even a helpline manned by a specialist nurse during office hours Monday-Friday.

There are lots of options for treatment available!

Learning to control antifungal drug resistance from the environment

Spores of fungi including Aspergillus fumigatus, the main species that causes aspergillosis, have been found to propagate the growth of strains of fungi that are already resistant to those antifungal medications most commonly used in medical clinics to treat aspergillosis. This can render the most common treatments for aspergillosis useless, which is a concern for doctors.

Where do these strains come from? Most experts suggest that the use of commercial fungicides by farmers exposes the fungus to pesticides that closely resemble the antifungal drugs used by doctors. This exposure is likely to enrich the numbers of resistant spores found in the environment ie in compost, soil, and of course in/on the plant material produced by the farmers e.g. food crops, and flowering plants.

Can we stop using these antifungal chemicals as pesticides? A multi-disciplinary meeting designed to bring together experts from all sides of the debate took place in London on 13th July and those representing the growers outlined how important it is that farmers use these fungicides to prevent crop damage and to produce enough food to feed us all! Completely stopping their use on crops does not seem to be an option.

Given that it seems that there will be antifungal-resistant spores in the environment we live in for the foreseeable future we need to:

- know where they are

- know how to avoid inhaling them

Where might patients come into contact with most antifungal-resistant spores?

Farmers use antifungal pesticides on many crops including:

- Fruits: Apples, grapes, peaches, strawberries, and tomatoes

- Vegetables: Potatoes, onions, corn, and soybeans

- Grains: Wheat, corn, and rice.

- Nursery crops: Roses, trees, and shrubs

Researchers have found antifungal-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus spores on many of these crops or the soil around them, at low levels (0 - 10% of samples).

Is this level of antifungal-resistant spores increasing?

When scientists looked at spore numbers they found that the number of resistant spores increased during the growing season as antifungal pesticides were applied to the crops, but this resistance did not survive the winter (1) and levels were back down to where they were the previous year.

It is apparent that handling crops, or the soil around them is a potential way to come into contact with some spores that are resistant to antifungal medications given in the clinic.

What is the likelihood of these spores causing an antifungal-resistant infection?

Researchers (1) have looked at how resistant the resistant spores are to the level of antifungal medication they will be exposed to in a patient and found that the proportion of the isolates that were resistant to the levels of antifungal medication used in patients was 1-4% - so very low.

Which crops are worst affected?

The most common material found to contain antifungal-resistant material was plant material waste originating from cut flowers and flowering bulbs and other types of waste produced in the industry in The Netherlands (2), so it is clear that composting can promote the growth of resistant spores. Ways to prevent this from happening are under development.

Other materials tested were household waste, wheat grain, poultry manure, cattle manure, horse manure, maize silage & fruit waste and of those antifungal-resistant spores were found only in fresh household waste.

Other researchers across the world (3) have detected antifungal-resistant spores in a range of crops and soils. Highest numbers of resistant spores (or perhaps in places where most research has been done) tend to be in India (rice), China (maize, some house plants, potato), USA (wheat, roses, apples), The Netherlands (orchids), Spain (onions, strawberries), Colombia (carrots) & Italy (grapes).

These were not exhaustive studies and we know that Aspergillus fumigatus (i.e. not antifungal-resistant) itself is found on far more plants/fruits/vegetables, so it stands to reason that if they are treated with antifungal pesticides then it may be possible to isolate resistant spores from them. It is clear that although there is a risk of inhaling antifungal-resistant spores from this plant material, the risk to the domestic consumer is low. Nonetheless, out of an abundance of caution, it might be best to take a few precautions:

a. Avoid handling cut flowers and flowering bulbs from The Netherlands

b. After purchase wash fruit and vegetables prior to storage in the home

c. Dispose of household waste in a timely manner

Action is being proposed and taken nationally and internationally to reduce the risk to aspergillosis patients in particular of inhaling antifungal-resistant spores of A. fumigatus and other fungi (4). Research is ongoing to learn more about what are the causal factors responsible for the increase in resistant spores, which are the main risks to human health and what we can do about it.

In time we should be able to prevent the growth of resistant isolates, ensuring that we have useful antifungal medication for years to come.

1. Effects of Agricultural Fungicide Use on Aspergillus fumigatus Abundance, Antifungal Susceptibility, and Population Structure

Authors: Amelia E. Barber https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3399-1037, Jennifer Riedel, Tongta Sae-Ong, Kang Kang, Werner Brabetz, Gianni Panagiotou, Holger B. Deising, Oliver Kurzai https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7277-2646AUTHORS INFO & AFFILIATIONS

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.02213-20

2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2019 Jul; 25(7): 1347–1353. doi: 10.3201/eid2507.181625

Environmental Hotspots for Azole Resistance Selection of Aspergillus fumigatus, the Netherlands

Sijmen E. Schoustra, Alfons J.M. Debets, Antonius J.M.M. Rijs, 1 Jianhua Zhang, Eveline Snelders, Peter C. Leendertse, Willem J.G. Melchers, Anton G. Rietveld, Bas J. Zwaan, and Paul E. Verweij

3. Azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus in the environment by cburks817 · MapHub

4. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022; 20(9): 557–571.

Published online 2022 Mar 29. doi: 10.1038/s41579-022-00720-1

Tackling the emerging threat of antifungal resistance to human health

Matthew C. Fisher,1 Ana Alastruey-Izquierdo,2 Judith Berman,3 Tihana Bicanic,4 Elaine M. Bignell,5 Paul Bowyer,6 Michael Bromley,6 Roger Brüggemann,7 Gary Garber,8 Oliver A. Cornely,9 Sarah. J. Gurr,10 Thomas S. Harrison,4,5 Ed Kuijper,11 Johanna Rhodes,1 Donald C. Sheppard,12 Adilia Warris,5 P. Lewis White,13 Jianping Xu,14 Bas Zwaan,15 and Paul E. Verweij11,16

Spring COVID Booster

COVID-19 levels of infection in the UK are far lower than they have been earlier in the pandemic, even while most people have returned to taking fewer precautions against infection. Increased immunity in the UK population caused by vaccination and infection has likely brought us to this better place.

However levels of immunity are not fixed and much like the common cold it gradually declines in each of us, leaving us open to re-infection within a year. Consequently, we must keep 'topping up' immunity in order to avoid severe symptoms should we be infected. For most of us that are now likely to be a natural process of periodic re-infection until the virus stops circulating so widely.

If you are in a highly vulnerable group it is safest to top-up your immunity without being infected by having a booster vaccination. The Uk government will launch a spring booster campaign shortly to address this need.

Those who will be offered this booster will only be the most at risk, so you may or may not be offered it depending on the opinion of your local hospital doctor or GP. The criteria for the spring booster seem to be more restricted than earlier boosters and will only be offered 6 months after your last booster.

Criteria for the spring campaign are:

- adults aged 75 years and over

- residents in a care home for older adults

- individuals aged 5 years and over who are immunosuppressed (Your doctor will get guidelines to decide this for you)

There will likely be a less restricted booster jab in autumn 2023 too.

Loneliness and Aspergillosis

[et_pb_section fb_built="1" _builder_version="4.19.1" _module_preset="default" custom_padding="0px||0px|8px||" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content" custom_margin="|59px||42px||"][et_pb_row _builder_version="4.19.1" _module_preset="default" custom_margin="50px|auto|50px|30px|true|false" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content"][et_pb_column type="4_4" _builder_version="4.19.1" _module_preset="default" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content"][et_pb_text _builder_version="4.19.1" _module_preset="default" custom_margin="|-124px||||" custom_padding="|0px||||" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content"]

Believe it or not, loneliness is as bad for your health as obesity, air pollution or physical inactivity. Some studies put loneliness as equivalent to smoking 15 cigarettes per day.

In a recent poll in our Facebook patient group for people with chronic forms of aspergillosis 40% stated that they were lonely more than once per week and 75% of those stated that they were lonely every day. In total 73% recorded loneliness at least occasionally.

We also asked people who care for aspergillosis patients the same questions and this time 56% stated that they were lonely more than once per week, with 78% lonely at least occasionally.

Give those two poll results, are people lonely because they have a chronic illness that might restrict their socialising, and are they lonely because they look after someone with a chronic illness?

The level of loneliness in the general population in the UK is currently at 45%, so there are clearly more people who are lonely in both groups affected by aspergillosis (73% and 78%). Furthermore, 30% of those people who have chronic aspergillosis in our poll were lonely every day, which compares poorly with national statistics that show the number of people in the general population who are lonely as frequently as every day is only 5%.

Conclusion: There are six times as many people with chronic aspergillosis that are lonely every day compared with the general UK population!

Loneliness is clearly a big problem for people who either have chronic aspergillosis or care for someone with chronic aspergillosis.

What can we do about this?

Firstly, awareness of the problem is a big step forward. Awareness of its far-reaching consequences for our mental and physical health may provide some incentive to take action to try to change things. The campaign to end Loneliness (https://www.campaigntoendloneliness.org/the-facts-on-loneliness/) has found that those affected can be of all ages/genders/able or disabled/chronically ill or not and they aim to inspire everyone to connect and communities to come together to help. Nobody should be without company who wants it.

They also provide a lot of useful hints and tips on how to reduce your loneliness (https://www.campaigntoendloneliness.org/feeling-lonely/ ), how to connect with others a bit better, and reduce your health risks – if nothing else at the moment we all could do with getting together to keep warm! Regardless of why you feel lonely, we can all find a way to make connections no matter how fleeting – they all count.

Here at the National Aspergillosis Centre we hold weekly meetings for all patients both here in the UK and abroad

Zoom meetings are a casual and fun way to chat with fellow aspergillosis travelers and NAC staff (Tuesdays 2-3pm GMT and Thursdays 10 – 11am GMT) in which you can just sit and listen to us all chatting for an hour – all you need is a smartphone/tablet/laptop to join us.

The meetings are private so we do not give instructions on how to join on a public page such as this. For directions on how to get involved join one of the following groups and we will get back to you:

Of course some people are entirely happy on their own

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

Managing Chronic Pain

[et_pb_section fb_built="1" _builder_version="4.19.1" _module_preset="default" custom_padding="3px|||2px||" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content"][et_pb_row column_structure="3_5,2_5" _builder_version="4.21.0" _module_preset="default" custom_margin="45px|auto|5px|auto|false|false" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content"][et_pb_column type="3_5" _builder_version="4.21.0" _module_preset="default" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content"][et_pb_text _builder_version="4.21.0" _module_preset="default" custom_margin="|-51px||||" custom_padding="|41px||||" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content"]

Chronic pain is common amongst people with chronic respiratory diseases, and also amongst their carers; in fact it is one of the most common reasons for both to visit the doctor. At one time your doctor’s response might have been simple – check that the cause of the pain should clear up with intervention and then prescribe painkiller drugs to help the patient cope with the short period of pain. If the predicted period of pain is not going to be short they might continue to give you painkillers, but after a certain point we know that two things start to happen:

- The painkillers will start giving you side effects, some of which can be serious (eg. depression). The longer you are on the painkillers, and the higher the dose, the worse this can get.

- Some painkillers – especially those used to treat severe pain – start to lose their effectiveness if given over several weeks

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][et_pb_column type="2_5" _builder_version="4.21.0" _module_preset="default" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content"][et_pb_image src="https://aspergillosis.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/managechronpain.jpg" title_text="managechronpain" align="right" _builder_version="4.21.0" _module_preset="default" custom_margin="|||-15px||" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content"][/et_pb_image][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][et_pb_row _builder_version="4.21.0" _module_preset="default" custom_margin="12px|auto|8px|auto|false|false" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content"][et_pb_column type="4_4" _builder_version="4.21.0" _module_preset="default" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content"][et_pb_text _builder_version="4.21.0" _module_preset="default" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content"]

Nowadays doctors are more likely to try and encourage patients to remain active, to remain at work and, depending on the source of the pain, might well recommend strengthening exercises (improved muscle tone and strength case help support a painful joint). This also helps the patient to socialise, reduces anxiety and the risk of depression, and can even reduce the pain itself.

But wait! You might ask: Won’t moving a painful joint cause more damage and therefore more pain? If done under medical supervision this is unlikely, and overall the pain usually improves and the dose of painkillers is reduced.

Find out more at: NHS – Managing chronic pain

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][et_pb_row _builder_version="4.19.1" _module_preset="default" custom_margin="16px|auto|-5px|auto|false|false" custom_padding="31px|4px|40px|4px|false|true" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content"][et_pb_column type="4_4" _builder_version="4.19.1" _module_preset="default" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content"][et_pb_text _builder_version="4.21.0" _module_preset="default" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content"]

But what about the chest pain often experienced by people with respiratory illness?

Firstly it is important to stress that all chest pain needs to be examined by a doctor as there are several possible causes and some causes need immediate attention e.g. heart attack!

Some chest pain comes from sore bones, muscles and joints so, as we cannot avoid moving our chests during breathing, we tend to reduce movement for a while and take painkillers until the pain is reduced. But, just as written above, your doctor may start to use a variety of approaches to keep your chest moving, build up the muscles to help prevent future pain, and reduce painkiller dose – the same as with any other joint pain.

Find out more at: NHS Chest pain

How can I reduce my dose of painkillers?

There are several techniques that will help you feel more in control of the amount of pain you are in – some are mentioned in the above link, managing chronic pain. Several exploit a little known fact about pain, which most of us will take some convincing of. Our pain is not generated by injury, it is generated by our brains as a defensive mechanism. That suggests that the amount of pain we feel is not inevitable, we might be able to control it a little by using our brains!

Not convinced? Try watching this video recommended by one of our patients, which helped her understand that we can do something to reduce our pain, and possibly even reduce our dose of painkillers.

[/et_pb_text][et_pb_video src="https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5p6sbi_0lLc" _builder_version="4.19.1" _module_preset="default" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content"][/et_pb_video][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

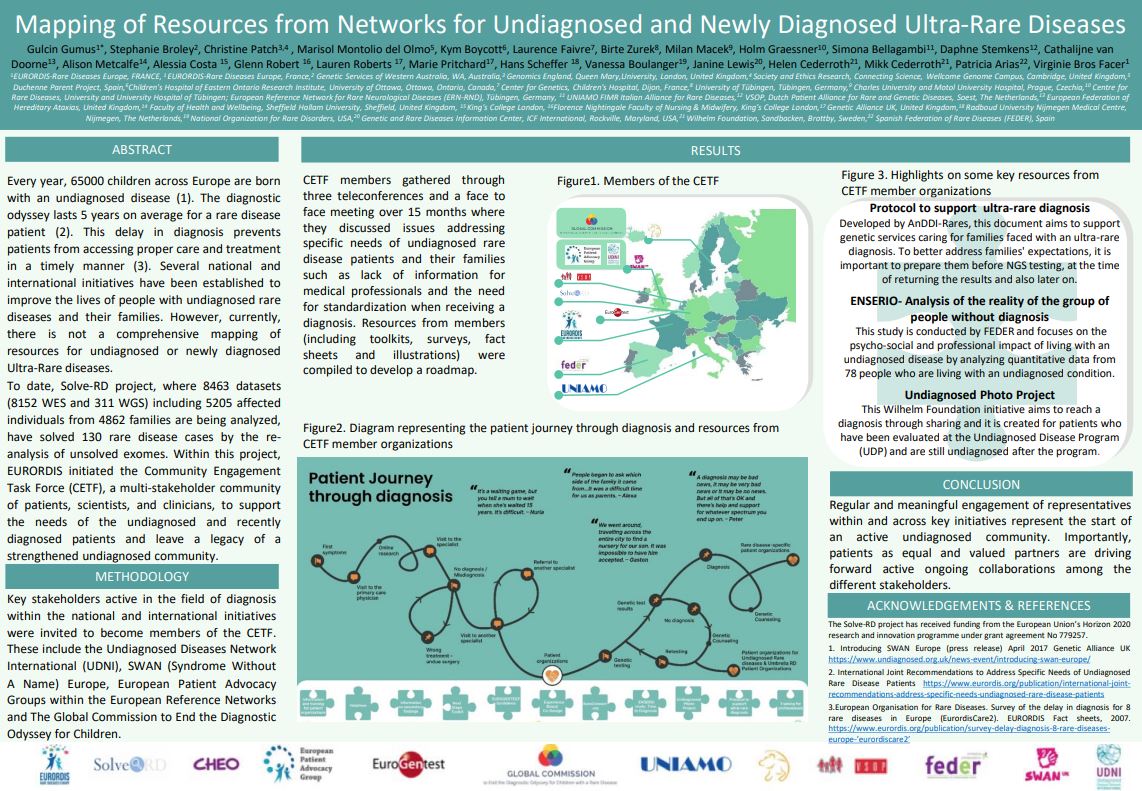

Rare disease patient journey to diagnosis

[et_pb_section fb_built="1" _builder_version="4.16" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content"][et_pb_row _builder_version="4.16" background_size="initial" background_position="top_left" background_repeat="repeat" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content"][et_pb_column type="4_4" _builder_version="4.16" custom_padding="|||" global_colors_info="{}" custom_padding__hover="|||" theme_builder_area="post_content"][et_pb_text _builder_version="4.16" background_size="initial" background_position="top_left" background_repeat="repeat" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content"]

A map aspergillosis patients may be all too familiar with!

https://twitter.com/eurordis/status/1269906129364156416

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]

Talking to Friends and Family about Aspergillosis

[et_pb_section fb_built="1" admin_label="section" _builder_version="4.16" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content" custom_padding="1px||1px||true|false"][et_pb_row admin_label="row" _builder_version="4.16" background_size="initial" background_position="top_left" background_repeat="repeat" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content"][et_pb_column type="4_4" _builder_version="4.16" custom_padding="|||" global_colors_info="{}" custom_padding__hover="|||" theme_builder_area="post_content"][et_pb_text admin_label="Text" _builder_version="4.16" background_size="initial" background_position="top_left" background_repeat="repeat" global_colors_info="{}" theme_builder_area="post_content"]

It can be hard to talk to friends and family about aspergillosis. As a rare disease, few people know about it, and some of the medical terms can be quite confusing. If you’ve been recently diagnosed, you might still be getting to grips with the disease for yourself, and learning about how it will affect your life. You might also run into preconceptions or assumptions about fungal disease that aren’t particularly helpful.

All in all, these are tricky waters to navigate, so here are some things to consider before talking to someone about aspergillosis for the first time.

- Get to grips with aspergillosis yourself first. Particularly if you’ve recently been diagnosed.

You might not ever know all the answers, but having an understanding of your type, your treatment and what aspergillosis means for you will help.

- Pick a good time and place. Being able to talk one-to-one, in a place where you won’t be interrupted, is a good first step.

It’s also a good idea to choose a time when neither of you will have to rush off. Pop the kettle on and settle in.

- Be patient. Your loved one or friend probably won’t have heard of aspergillosis before, and might struggle with the different medical words, so give them time to digest what you have told them and ask questions if they need to.

Try not to get frustrated if they don’t react in the way that you’d hoped. They might be very sad, when what you need right now is someone to be strong. Or they might brush it off or make light of it, when you want them to understand that aspergillosis is a serious disease. Often people need time to go away and think before coming back with offers of support, or with more questions – let them know that that’s ok.

- Be open and honest. Talking to someone you care for about the disease is not easy, but it’s important that you explain how aspergillosis is likely to affect you. You might feel tempted to downplay things, but being honest can help in managing your friend or family member’s expectations in the future.

Some people find the Spoon Theory helpful in explaining chronic illness. In short, spoons represent the energy needed to get daily tasks (getting dressed, showering, washing up etc.) done. People without chronic illness have an unlimited number of spoons each day. But people with a disease like aspergillosis only get, say, 10 spoons on a ‘good’ day. Using this example can help to explain how living with aspergillosis effects all areas of life.

- Let them in. If you are talking to someone close to you, inviting them to learn more or share some of your experiences can be very helpful. You might want to invite them to come to an appointment with you, or visit a local support meeting.

If they want to learn more, or ask questions you don’t know the answer to, useful resources are available online. For example, did you know that we have a Facebook group just for family, friends and carers of people with aspergillosis? Lots of pages on this website can also be very helpful, so feel free to pass on the link (https://aspergillosis.org/).

- Be yourself – you are not your disease. There is so much more to you than aspergillosis, and your friends and family should know that too. But talking about it could mean that you get a little bit more support or understanding from those closest to you, which is never a bad thing.

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]